[ad_1]

Even as designers’ creativity comes alive with 3D-printed clothes and jewellery at a fashion show, elsewhere in the world a cancer-ridden bird stays alive with a 3D-printed bill, and a new-born child gets a new lease on life with a 3D-printed skull. Indeed, the emerging applications of 3D printing are awe-inspiring and packed with hope

Crescent, a 25-year-old Great Indian Hornbill, is one of the most loved birds in ZooTampa at Lowry Park, Florida (USA). When the zoo officials posted a picture of this winged beauty on their Instagram page last year with the tag line, “Crescent, our Great Indian Hornbill never misses a chance to strike a pose. Come out and visit her in our main aviary…,” little would they have thought that she would be inflicted by a potentially fatal form of skin cancer called squamous cell carcinoma.

While the tumour is typically found near the front of the casque in hornbills, hers was in the back. This almost ruled out the possibility of a traditional extraction, as it would have exposed the bird’s sinuses. So, a team at the University of South Florida’s Radiology department printed a new casque using a Formlabs 3D printer and their new BioMed White Resin, a photocurable material that can be used to print biocompatible parts for prosthetic devices.

The material had just been developed by Formlabs, and they donated it to the team trying to help Crescent. The team not only printed a new casque but also a replica of Crescent’s head so that the team of veterinary surgeons could try the operation virtually before performing it on the bird—as it was a rare procedure, which had been done only once before by a veterinary surgeon in Singapore.

In January this year, the team removed the tumour and fitted the new casque on Crescent, who is now back in the aviary—as perky as ever. Luckily, it turned out that the resin was a perfect match for the yellow preening oils that keep a hornbill’s casque bright and shiny, so she also looks as pretty as ever!

As against the early days of 3D printing, or additive manufacturing, when objects could be created only with a few polymer based materials, we now have advanced processes that enable 3D printing with dozens of materials ranging from carbon fibre composites, metals and alloys to sand, tungsten filament, and bio-compatible materials. Understandably, the applications and possibilities have also expanded manifold.

Industry 4.0 is gearing up to use additive manufacturing capabilities to print tools and jigs, and end-use components too. The energy sector is using additive manufacturing to print parts for customised solutions, while carmakers are using it to customise luxury cars. The aerospace world is using it extensively to print lightweight but sturdy parts and components from special materials, while the food industry is using it to make customised confectioneries and personalised nutrition solutions.

| 3D Printing: A Quick Background |

| 3D printing, or additive manufacturing, is a technology that has been developing slowly and steadily since the 1980s. In simple terms, a 3D printer can take CAD file as input and print a three-dimensional object by depositing layer after layer of a suitable material. Hence, it is known as ‘additive’ manufacturing. In some rare cases that require extreme precision, a subtractive process might also take place, where excess material is shaved off the object. Over the years, several technologies have emerged, capable of printing with different materials, and with varying degrees of precision. Each generation, or each new process, aims to bring down the manufacturing time and costs, increase the precision, and widen the spectrum of materials that can be used. Now, materials ranging from gypsum and ceramic to wood and titanium are being used for 3D printing. As a result, the potential applications are also increasing. |

From construction to electronics, everyone seems to be exploring how they can utilise the potential of 3D printing. Let us share some of those insights.

Print a pill? Old news! Ready to print organs now

According to a report by Grand View Research, an India and the US based market research and consulting company, the global healthcare additive manufacturing market size was valued at US$1.6 billion in 2021. It is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 22.6% from 2022 to 2030. The need for customised medical equipment like implants, the emergence of new 3D printing technologies that can economically print complex designs, and development of new biocompatible material capable of printing tissues, organs, dental fittings, orthopaedic and cranial implants are contributing to this growth.

Medical equipment like implants is very expensive to produce with traditional equipment, moulds, dies, and all the works. After all, most of these are comparable to works of art, tailor-made to fit a person. On top of that, these have to be produced quickly; sometimes it is a matter of life and death. The ability to swiftly develop prototypes using computer-aided design (CAD) makes 3D printing fast and economical.

Helping hand during the pandemic

3D printing rose to the occasion to support healthcare systems during the Covid-19 pandemic. Lockdowns crippled supply chains, but there was a growing need for supplies like personal protective equipment (PPE). 3D printing enthusiasts from around the world, university labs, and companies that had 3D printers started meeting this demand by printing goods like face shields and valves for respiratory machines. For example, 3T Additive Manufacturing Ltd and EOS produced more than 100,000 face shields for healthcare workers in the UK. Allevi Inc, a 3D bio-fabrication company, produced a model of the lungs of a person infected with SARS-CoV-2, which was studied by researchers at the Wistar Institute to understand the condition and find ways to treat and prevent it.

Prosthetics and exoskeletons

Earlier this year, 3D printing saved the life of a baby girl born with a critically-underdeveloped cranium—in simple terms, without a skull. A doctor approached Sygnis, a Polish deep tech company, just hours before the baby was due to be born. Armed with imaging data, Sygnis started 3D printing the skull using two different technologies, in case one failed. Within a day, they had the model ready—and the doctors completed fitting it within four days. The baby will require further treatment as she grows, and hopefully tech will find a way to help her survive.

Recently, Sygnis also produced another pre-operative model—the spine of a young child with meningo-spinal hernia and scoliosis.

3D printing is also proving to be very effective in the manufacture of exoskeletons for rehabilitation. 3D-printed exoskeletons are lighter, more durable, lower in cost, and a perfect fit for the person.

| 3D Printing Technology | Materials | Applications |

| Sheet lamination methods, such as ultrasonic additive manufacturing and laminated object manufacturing | Paper, plastic, metal, any sheet material that can be rolled | Non-functional prototypes and models, multi-colour prints, casting moulds |

| Directed metal deposition (DMD) or directed energy deposition (DED) | Metals like cobalt, chrome, titanium | Repairing high-end components, functional prototypes |

| Material extrusion, most common being fused deposition modelling (FDM) | Plastics and polymers, including polylactic acid (PLA), polycarbonate, acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), nylon, polyetheretherketone (PEEK), thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) and thermoplastic elastomer (TPE), carbon fibre filament | Electronic housings, form-fitting fixtures, investment casting patterns |

| Material jetting, nano-particle jetting, drop-on-demand | Plastics, polymers, silicone, metals | Prototypes, medical models, design presentations |

| Binder jetting | Polymers, metals, ceramics, glass | Metal parts, low-cost prototypes, sand casting moulds |

| Vat photo-polymerisation, such as stereolithography (SLA), direct light processing (DLP), and continuous direct light processing (CDLP) | Plastics, polymers, resins | Injection moulds, prototypes and models, dental fixtures, medical parts |

| Powder bed fusion technologies, including direct metal laser sintering (DMLS), electron beam melting (EBM), selective heat sintering (SHS), selective laser melting (SLM), and selective laser sintering (SLS) | Powder-based polymers and metals, including nylon, PEEK, non-toxic plant-based resin, stainless steel, titanium, aluminium, cobalt, chrome, copper, Alumide (a composite of aluminium and nylon), and Inconel (an alloy of chrome and nickel) | Functional metal parts, low-volume production, hollow designs |

There are also some open source projects, which aim to make low-cost 3D-printed prosthetics available to underserved populations across the world. Cyborg Beast, for example, is a low-cost 3D-printed prosthetic hand for children with upper-limb reductions. The designs are available under a Creative Commons license, so anyone can download, customise, and 3D-print them.

| 3D Printer in Space |

| According to a recent news report, aerospace company Airbus is planning to send a metal 3D printer, Metal3D, to the International Space Station (ISS) in 2023, as part of its plans to establish an orbital satellite factory. According to Airbus, this will be the first metal 3D printer on the ISS. It will enable astronauts to print tools and parts like radiation shields. The company also says in the media report that future versions of the printer will be able to create objects out of lunar soil and recycle parts from decommissioned satellites onboard an orbital satellite factory. |

According to the Biomechanics Department of the University of Nebraska Omaha, the majority of the required materials are available at local hardware stores or online, costing approximately US$50. It takes around 2.5 hours to assemble the prosthetic hand, which weighs less than 200 grams. A similar device (made using traditional methods) would cost approximately US$4000 and weigh about 400 grams.

Blood vessels, tissues, and organs too

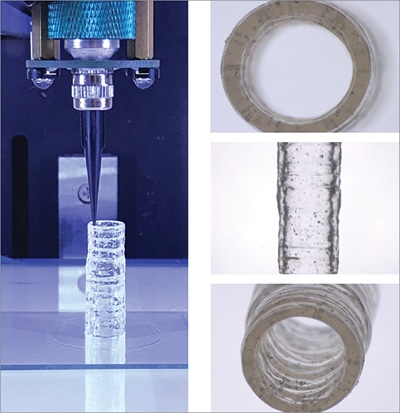

The emerging space of 3D bioprinting involves printing with cells and biomaterials, creating organ-like structures that let living cells multiply. These tissues and organ models help to understand diseased conditions better (for drug development) and for potential treatment.

Scientists at Technion-Israel Institute of Technology have created a hierarchical network of 3D-printed blood vessels capable of supplying the necessary amount of blood to an implanted tissue. For a tissue implant to be successful, it must first be permeated by the body’s blood vessels for it to receive the required oxygen and nutrients. To achieve this, the tissue is first implanted in a healthy limb of the patient’s body, and then shifted to the required location. This complicates and delays the process.

At Technion, the scientists have created a tissue flap in the lab, with all the vessels necessary for blood supply, so it can directly be implanted in the affected area. The new tech has been successfully tested on rats and will be tested on larger animals before it is ready for human use.

While previous experiments used collagen from animals in the bio-ink, here, Israeli company CollPlant Biotechnologies has genetically engineered tobacco plants with five human genes to produce collagen! According to the researchers, large blood vessels of the exact shape necessary can be printed and implanted together with the tissue that needs to be implanted. This tissue can be formed using the patient’s own cells, eliminating rejection risk.

A team of researchers led by associate professor Dr Akhilesh Gaharwar and assistant professor Dr Abhishek Jain, in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Texas A&M University, have designed a 3D-bioprinted model of a blood vessel in healthy and diseased states. They have also developed a new nanoengineered bio-ink, which has the strength and optimal viscosity for smooth printing. The ink is printed into 3D cylindrical blood vessels, consisting of living co-cultures of endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells, which maintain integrity of the arterial walls.

The best part is that they have customised a US$200 off-the-shelf thermoplastic printer into a bioprinter, saving thousands of dollars. This scientific development will help in research, treatment, and development of drugs for cardiovascular diseases.

With calcium phosphate as material, it is now possible to print bones, which unify within weeks after grafting, with low rate of rejection by the body. Quite recently, researchers at Princeton University 3D-printed a bionic ear with above-average hearing abilities, demonstrating the possibility of creating bionic organs by combining biological and nano-electronic functionalities through 3D printing.

Scientists and companies around the world have shown that it is possible to 3D-print several parts of the human body today, from skin to eye lenses and jaw bones. In addition, researchers are also investigating the possibility of bio-ink infused with stem cells, which when injected in a scaffolding could help an organ to grow or regenerate.

Personalised surgical instruments

When compared to exoskeletons and organs, this might see less fantastic, but 3D-printed surgical instruments are equally critical in the life-saving journey. With 3D printing, it is possible to rapidly prototype and develop personalised surgical instruments at a very affordable cost point. Highly miniaturised instruments can also be 3D-printed, helping the surgeon to perform more precise surgeries. Companies like Formlabs and EOS are also into printing surgical instruments.

Sowing the seeds of innovation in India

Very recently, the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru, partnered with CELLINK—a global leader in 3D bioprinting—to establish a Centre of Excellence (CoE) for 3D bioprinting in India. The CoE will be situated at the Centre for Bio Systems Science and Engineering (BSSE) at IISc and will house several CELLLINK 3D bioprinters.

The Centre will provide researchers with quick access to 3D bioprinting systems, accelerating their efforts. It will also spearhead research and training initiatives related to the applications of 3D bioprinting in fields like tissue engineering, drug discovery, material science, and regenerative/personalised medicine. There will be a special focus on the heart, bone cartilage, and cancer.

Light and strong parts for cars and crafts that fly

The automotive and aerospace industries have also recognised the benefits of 3D printing and started adopting the tech, especially for low-volume, customised parts.

A Ford plant near Cincinnati saved millions of dollars by 3D printing a couple of expensive and hard-to-get spares, like pucks and bumpers. A General Motors facility in Tennessee also experienced significant savings by replacing conventional tooling components with 3D-printed alternatives made in-house. The 3D-printed tooling had better functionality despite being developed faster and at a lower cost.

The kind of design freedom that 3D printing gives is a boon for carmakers, especially in the luxury segment. Carmakers like Bentley are increasingly turning to 3D printing to customise their offerings and give customers exactly what they want.

With 3D printing, auto-makers can also ensure a proper supply of parts to customers, even those that went out of production years ago. This is a dream-come-true for vintage car and bike collectors, who are now able to restore and preserve their old models in working condition. Service centres in remote areas could also benefit by the ability to 3D-print spares instead of waiting for them to arrive from faraway warehouses.

3D printing is a real disruptor in the racing world, where aerodynamically-optimised parts with the right materials and designs can clinch a win. It is not surprising that most racing specialists today have partnered with 3D printing firms—Ducati Corse with Roboze, Alfa Romeo with Additive Industries, EOS with the Camozzi Group, NASCAR with Stratasys, and so on.

Several parts, ranging from brake ducts, brackets and supports, to seals and cockpit ventilation systems, are being 3D-printed today. Material innovation is also at its peak in this space—new composites are giving these cars and bikes the right mix of strength, weight, and temperature tolerance.

If these factors are so important for automobiles, you can easily imagine how critical they would be for aircrafts and spacecrafts. No wonder then that the aerospace industry is an eager taker for this tech. Additive manufacturing is being used to print a lot of stuff, from jigs and fixtures to surrogates, mounting brackets and detailed prototypes.

The tech is helping engineers make lighter and more efficient engines and turbine parts. The ability to print replacement parts reduces downtime and also extends the life of aircrafts, as even obsolete parts can be upgraded to current standards and 3D-printed.

A Dassault Systèmes report recalls how Satair, an aircraft component and service company based in Denmark and a subsidiary of Airbus, provided one of its airline customers in the US with a 3D-printed spare part in 2020. The part was no longer being produced by the original supplier. Redesigning it and producing it using conventional methods was an expensive proposition. So, using a new certification process, Satair was able to recertify the former cast part within five weeks and adapt it to titanium, a material well-suited for additive manufacturing and for use in aircrafts. The part was then 3D-printed and supplied to the obviously happy customer!

Interestingly, additive manufacturing is used extensively to print parts of cabin interiors like seats and handles—in an effort to reduce weight while maintaining aesthetics. Reducing weight helps reduce air drag, saves fuel, and correspondingly carbon dioxide emissions too.

The Peekay Group in association with Bengaluru Airport City Limited (BACL) has set up a new state-of-the-art 3D printing facility at the Airport City. It has a production centre and an experience zone, where individuals and students can come and try their hand at 3D printing. It will also incubate worthy projects.

The Peekay Group also plans to install a 3D metal printing unit to cater to the aerospace industry. They hope to add more 3D printing processes, so students can get more experience in environment-friendly, design-oriented manufacturing, while technicians can also upskill themselves.

Your building, as you like it, as fast as you want it

In April 2021, Tvasta Construction, a startup incubated at IIT Madras, built a 56 square metre (600 sq ft) house on the university campus. The quaint house has a hall, a kitchen, and a bedroom. Sounds normal? Well, what makes it special is that it was built within five days using concrete 3D printing technology.

More recently, the Indian Army’s Military Engineering Services (MES) partnered with Tvasta to 3D-print two houses for soldiers at the South-Western Air Command, Gandhinagar, within a month’s time. The 65 square metre (700 sq ft) homes are designed to be disaster-resistant and meet Zone-3 earthquake specifications. They also 3D-printed sanitary blocks with a total built area of about 56 square metres at Jaisalmer.

The startup works closely with the Central Building Research Institute and Structural Engineering Research Centre to ensure that the 3D-printed structures meet required safety standards. But houses are not all that they can build. They have even been asked to build bunkers and parking facilities at border areas, where traditional construction is a challenge due to the harsh weather and hostile conditions!

Similarly, the US Department of Defence (DoD) is building three training barracks in Texas using 3D printing tech, with private partnership. Each barrack will be more than 530 square metre (5700 sq ft) in size, making these the largest 3D-printed structures in the US. It will be printed using a proprietary high-strength concrete, capable of withstanding the harsh desert weather.

Back home in Bengaluru, we hear that an entire three-storied post office is going to come up in Halasuru within a month or so. The project will be completed using 3D printing technology by Larsen & Toubro Construction at just 25% of the normal construction cost.

For jawans and green warriors, foods, and fundas

3D printing is finding some use or the other in many fields, and it will not be long before these disparate applications unify into large-scale adoption.

Defence

Although 3D printing is not widely used for critical military equipment, it supports the army in many ways. We already read about housing, barracks, and bunkers being built using 3D printing technologies.

3D printing is also used to print armour suits, and parts used in aircraft engines, tanks, and submarines. Recently, the US DoD announced that it plans to pair defaulting suppliers with 3D printing companies that can print metal parts, so they can quickly get over the backlog.

Like in other industries, 3D printing is also used extensively for prototyping and testing military equipment. The Indian army is also collaborating with many Indian 3D printing companies like Chennai based Tvasta Constructions and Mumbai based Divide by Zero.

Researchers at IIT Jodhpur have recently developed a metal 3D printer suitable for repairing and adding additional material to existing components. It can print with metal powders made in India and is considered ideal for printing fully-functional parts for aerospace, defence, automotive, oil, gas, and other industries.

Energy

Benefits like design flexibility, short time-to-market, lighter and better performing parts, reduction in material wastage, elimination of supply-chain issues, and tool-free production are leading several companies in the energy sector to deploy 3D printing solutions. Most market leaders—including BP Global, Chevron, Exxon Mobil, GE Power and Shell Global—are using 3D printing.

Earlier, 3D printing was used only for prototyping and not for end-use components. But, with the ability to print with more materials, it is being used to print various goods like solar panels. According to a report by GE Research, 3D-printed solar panels have proven to be 20% more efficient than traditional ones, and at half the price of manufacturing.

3D printing is also used for manufacturing high-value, high-complexity, low-volume components, like gas turbine nozzles, impellors, pistons, pumps, rotors, and parts for control valves, flow meters, heat exchangers, and pressure gauges. The cost of downtime is very high in the energy sector and failure can occur even in remote areas. The ability to print spares will help reduce downtime without stocking up on spares.

Robotics

3D printing is a boon for robotics enthusiasts in countries where components are not easily and economically available. Since many component designs are available online under free or open source licenses, enthusiasts with access to 3D printers can easily print these components and use them in their projects. Even if they are unable to own one individually, groups of enthusiasts can pool in and share 3D printers.

In fact, it is this need that motivated the founders of Divide by Zero to float a 3D printing startup. They used to enter a lot of robotics contests when they were in college and were in trouble each time a robot needed a spare. No machine tool shop was ready to manufacture one or two pieces and, even if they did, they used to charge them heavily.

This motivated them to develop an indigenous 3D printer such as the Accucraft i250+. “We thought of making affordable 3D printers for the Indian market and support individuals and organisations to prototype their ideas, play with them and create wonders,” said one of the founders in an interview. The inherent benefits make 3D printing attractive to hobbyists and the industry alike.

Openbot by Intel and Atlas by Boston Dynamics are some of the well-known 3D-printed robots, not to forget the emerging range of 3D-printed humanoids, swarms, amphibious and other bio-inspired robots. 3D printing of soft robots from non-toxic, gelatin based material is gaining popularity of late for applications like teaching and training children, food manufacturing, consumable biomedical test equipment, and so on.

3D printing plus Arduino is an all-time favourite combo of hobbyists, and you can find several robots ranging from cute to chunky on Instructables and Thingiverse. Do check out the lovable dancing robot Tito, the spider-like Hexapoduino, the handy MeArm V0.4, and more such projects online.

Others

You eat the food with your eyes first, goes the adage. It is therefore not surprising that the food industry has been quick to pick up 3D printing techniques to create visually-appealing foods like never before. 3D printing is used widely to produce small batches of customised foods, and for creating personalised nutrition packages.

3D printing is also a wonderful learning tool. Around the world, schools and colleges are using 3D printing to print a range of models from historic monuments to functional parts, to help students understand concepts better.

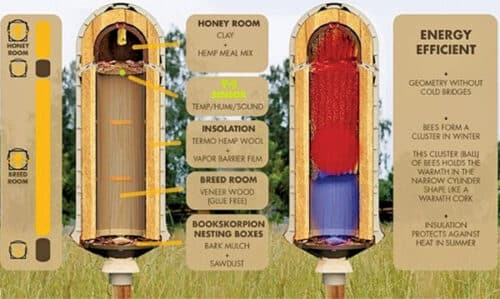

It is also finding innovative uses in farms. In Germany, for example, a startup called HIIVE is 3D printing tree cavities for bee farms. Honeybees like the Apis Mellifera originally live in tree cavities, which have a special microclimate that is not only good for bees but also for beneficial symbionts that co-inhabit the tree cavities with the bees.

Using a close-to-natural hive, bee farms can attract more bees, and get a better harvest, while also ensuring a natural habitat for the bees. A symbiotic deal indeed. 3D printing made it possible for HIIVE to iteratively tweak the design to develop an optimal structure for the tree cavities, which are 3D-printed with multiple natural materials.

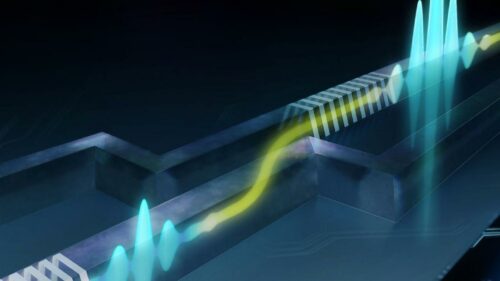

3D printing also enables a lot of innovation and optimisation in the electronics industry. Rapid prototyping and the ability to manufacture small batches of electronics at a lower cost is a boon for all consuming industries. 3D printing is also said to be more eco-friendly, as it generates much less e-waste as compared to the traditional etching processes. The ability to print on non-flat surfaces and on varied materials, including plastics, opens up new opportunities for innovation.

Space Foundry, a company launched by former NASA researcher Ram Prasad Gandhiraman and Dennis Nordlund of Stanford University, has created a plasma based 3D printing process, which can print electronics in a single-step approach that does not require heat or ultraviolet curing. The multilateral printing platform can print various materials, including metals like copper, dielectrics, organics and even bioinks. It is an environment-friendly process that does not leave behind liquid industrial waste or toxic by-products.

NASA believes this tech can enhance its in-space manufacturing efforts through on-demand manufacturing of electronics (ODME), as plasma jet printing can potentially be used for manufacturing in the low Earth orbit and on the lunar surface. In a press report, Gandhiraman describes their 3D printer as a highly miniaturised version of semiconductor manufacturing technology.

As a service

While we do see random use of 3D printing in almost all industries, it is yet to gain traction in mission-critical applications, as certification and part qualification processes are still not in place. For rapid prototyping and testing, or for one-off production needs, it does not make sense for small companies to invest in 3D printing setups. However, everyone would be happy to have a go at it, if available as a service. There are many companies offering 3D printing as a service, and this is likely to remain the popular choice in the near future too.

| 3D Printer in Space |

According to a recent news report, aerospace company Airbus is planning to send a metal 3D printer, Metal3D, to the International Space Station (ISS) in 2023, as part of its plans to establish an orbital satellite factory. According to Airbus, this will be the first metal 3D printer on the ISS. It will enable astronauts to print tools and parts like radiation shields. The company also says in the media report that future versions of the printer will be able to create objects out of lunar soil and recycle parts from decommissioned satellites onboard an orbital satellite factory. |

3D printing just right for Atmanirbhar Bharat

Recognising the scope of 3D printing, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) released the National Strategy for Additive Manufacturing earlier this year. The ministry hopes to increase India’s share in the global additive manufacturing to 5% by 2025. The national strategy sets various goals for the industry in this direction—to add US$1 billion to the gross domestic product; develop 50 India-specific technologies for material, machine and software; setup 100 new start-ups for additive manufacturing; develop 500 new products; train at least 100,000 new skilled workers, and so on, in the next three years.

The strategy recommends that India must come forth and adopt additive manufacturing in all sectors, including defence and public sectors. Adoption of 3D printing on an industrial scale could help domestic companies to overcome technical and economic barriers—and tread proudly on the path of a self-reliant India!

Janani G. Vikram is a freelance writer based in Chennai, who loves to write on emerging technologies and Indian culture. She believes in relishing every moment of life, as happy memories are the best savings for the future

[ad_2]

Source link